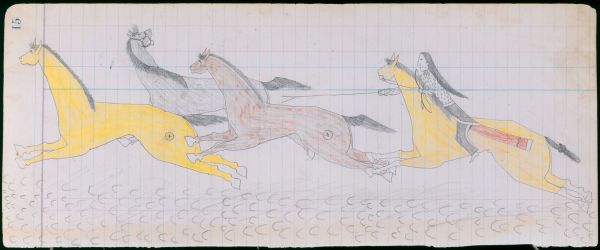

PLATE 15

Ethnographic Notes

In addition to the troublesome hide hunters, gangs of White horse thieves using Dodge City as a base began raiding the Cheyennes in the early-1870's. George Bent, who was then working as interpreter for the Cheyenne Agency, and who lost his own herd to White thieves in the spring of 1874, remembered:

"There was not much law on the border at this time for anyone, and none at all for the Indian. Had the military authorities, in protection of the Indians on reservations, but expended a fraction of the money later spent in putting down Indian uprisings, a different story might be told" (Hyde, 1968: 354).

Soon after the Cheyenne chiefs had returned from their trip to Washington, where President Grant had promised they would be protected from the dual plague of hide hunters and horse thieves, nearly the entire herd of Chief Little Robe's camp was stolen, well over a thousand animals (Hyde, 1968: 355; Collins, 1928: 132). Although Little Robe had dedicated himself to peace with the Whites, he was one of the most respected chiefs of the Dog Soldier Society, and his camp was then the largest among the Southern Cheyennes: 262 lodges (Moore, 1987: 199 & Map 14).

Fifteen young warriors on the best remaining horses followed the thieves nearly to the Kansas line, but could not recover the herd. Many cattle companies and small, independent ranchers, also in violation of the 1867 treaty, were moving south of the Arkansas River at this time, and staking out the section of country through which the famous Dodge City cut-off of the Chisholm Trail would soon be blazed. As the dejected young Cheyennes were returning south they encountered some of these interlopers, rounded up several herds of their horses, and proceded homeward. Fairly soon they had nearly a thousand head of horses, and a posse of angry cattlemen hot on their trail. An Army patrol out of Fort Dodge was alerted by some of the ranchers, and joined the pursuit of "the Indian horse thieves". By the time the Cheyennes approached the Cimarron River, twenty miles from Little Robe's camp, they were driving the herd on a dead run, with their pursuers only minutes behind.

As a young man in 1883, Hubert Collins had the details of this story from Chief Little Robe, and from his son who accompanied the Cheyennes pursuers (named Sitting Medicine, according to Hyde, 1968: 355). Part of that account is appended here, because it describes so exactly this drawing, which also portrays an event of 1874:

"[Out of] a great and fast moving cloud of dust...came the thunder of a...fan-shaped herd of ponies running at break-neck speed. Muzzles stretched out in front, tails straight out behind, ears laid back, legs doubling under like jack-knives to reach the longest strides, bodies almost touching the ground, the whole herd came on in full stampede.

"It was a controlled stampede, however, for they headed in a straight line for the [ford of the Cimarron]. Through the dust cloud the forms of fifteen Indian youths could be seen driving and directing the herd. Each rode a pony stripped for war, guiding him with knee pressure. Every man of them was wielding his quirt unmercifully, both on his ridden mount and on the driven ponies as well. Bent forward, hair flying, arms and bodies rising and falling in regular rhythm, men and animals made a composite picture of deadly earnest action. The roar of the herd's hooves drowned all other sounds" (Collins, 1928: 131).

After the herd was crossed, young Sitting Medicine stayed back alone to hold the ford against the forty, well-armed Whites. Charging his horse back and forth on the far bank of the Cimarron he defied the posse, which scattered out along the river. The forty marksmen fired at the Cheyenne for several minutes until they killed his horse, then wounded Sitting Medicine twice, breaking an arm and one of his legs, leaving him unconscious. Perhaps suspecting a trap, and with darkness approaching, the forty soldiers and cattlemen abandoned the pursuit, out-bluffed by a courageous Cheyenne warrior lying unconscious near the river.

When the other Cheyennes reached home with their captured horses, and news that Sitting Medicine had stayed behind, Little Robe started immediately for the river crossing. The next morning he found his wounded son and brought him home, where he was nursed back to health (Collins, 1928: 131-139).

In addition to Little Robe's son, Collins names four of the other young men who tried to track down and recover the tribe's stolen horses in the spring of 1874. These he gives as "Okerhater, the Cheyenne sub-chief", "Taawaytie, the Comanche" (visiting when the raid occurred), "Ohstei" and "Zotom". This is a very significant group to be associated together at this time, for a year later, after hostilities had been concluded, all four would be sent as prisoners-of-war to a three-year exile at Fort Marion, Florida, where three would gain renown as accomplished artists.

"Oakerhater" is the same "O-kuh-ha-tuh" of the Fort Marion prisoners, called Making Medicine (Pratt, 1964: 139), later called David Okerhater, and David Pendleton (Petersen, 1971: 225). Making Medicine---his name was actually Sun Dancer, Oxhehetan (Petter, 1915: 1029), a Bowstring Society officer, was leader of the party that replaced the horses stolen from Little Robe's people.

"Taawaytie" is the same "Taawayite", the Comanche prisoner at Fort Marion, later called Henry Pratt (Petersen, 1971: 176, 184). "Okstei" is the same "O-uk-ste-uh" at Fort Marion, called Shave Head (Pratt, 1964: 139; Petersen, 1971: 244). "Zotom" is the same "Zo-tom" at Fort Marion, called Biter (Pratt, 1964: 142; Petersen, 1971: 171-72). He was a Kiowa who, like Taawaytie, was visiting the Cheyennes when the White gang of horse thieves struck. In 1874, Making Medicine was 30 years old, Shave Head was 20, Zo-tom was 21, and Taawaytie was 19---all young men.

Much has been written about these Fort Marion prisoners, and their brilliant artistic abilities, including biographical treatments of Zo-tom and Making Medicine (Dunn, 1969; Petersen, 1971; Viola, 1998). At the time these men were imprisoned, the crime alleged against the two Cheyennes was that they were "ringleaders" (Pratt, 1964: 179). It has been suggested that a drunken Army officer grabbed them at random for deportation (Hyde, 1968: 365); but it would seem too coincidental that all four of the men who were along on this attempt to recover their stolen horses should have been seized. This raises the probability that names of those involved in this storied adventure---who were recognized as great heroes, and lauded by all Cheyennes---had filtered to the military authorities. Probably urged by irate demands from cattlemen whose own horses had been lost, the Army may have specifically targeted members of the tracking party for punishment.

Perhaps some of the other very young Cheyennes deported to Florida as "ringleaders" were also among those who shared in this great exploit: Howling Wolf, then 24 years old; Little Chief, 20 years of age; Roman Nose Thunder, Big Nose and Buzzard, each 19 years old; Matches and Squint Eyes, only 18 and 17 years old, respectively (Pratt, 1964: 139-140).

That would bring the total of known members of the tracking party to twelve. George Bent, who gave a slightly different version of events, names another: Curious Horn, also called White Bear (Hyde, 1968: 355). He may have been the White Bear killed at Sappa Creek, Kansas, in April 1875 (Hyde, 1968: 368-69), or more likely the Arapaho White Bear who was sent to Fort Marion (Pratt, 1964: 140; see the photo in Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 7).

Of the two other trackers, nothing has been known until now. It seems clear that Arrow, as accomplished an artist as the others, who here pictures himself helping to run off a very large number (note the tracks) of branded horses in 1874, was also along on this dangerous enterprise. Further evidence showing that Arrow and Making Medicine were associates appears in a famous drawing by Making Medicine, where Arrow is identified by the same name glyph he uses for himself, and is depicted carrying the otter-wrapped straight lance of the Elk Society (see Petersen, 1971: Color Plate 1; also, Ewers, 1968: Fig. H).

Considering now Arrow's own drawing of the horse raid, Plate 15, note that the appearance of both horse and rider indicates an abrupt departure. That is, the Cheyennes are here reacting to a situation for which they did not have time to properly prepare. Rather than wrapping the horse's tail and decorating it for combat, Arrow has merely tied an overhand knot in the hair. Nor did he have time to get his silver-mounted headstall. The horse has been quickly fitted with the type of war bridle described earlier by Wooden Leg (see Plate 6, above; and Marquis, 1931: 243-44), where a loop was made in the end of a rawhide lariat to form the reins, part of this loop was twisted around the horse's lower jaw, and the other end of the lariat was coiled, and tucked under the rider's belt.

One expression of mystical protection, however, has been vouchsafed the buckskin horse, and we shall see it frequently hereafter, for Arrow quickly adopts it as an identifying motif: a small, white feather with black tip, attached to the horse's tail. This appears to be a secondary feather of either a golden eagle or a rough-legged hawk, and may have been trimmed to this shape. In some depictions it could be confused with the ear of a jack rabbit, which might reasonably have been chosen as a talisman to promote speed. However, in Plates 72, 86 and others, the dark end is shown very wide and square, whereas a rabbit's ear is pointed. It seems most likely this talisman is related to the rough-legged hawkskin which Arrow wears tied to his scalplock in Plates 2 & 13.

In the drawing, Arrow's hair is uncombed and flying loose, suggesting an early-morning departure in haste. When the Cheyenne camp at the Little Bighorn was attacked in 1876, Wooden Leg had the same problem preparing for battle:

"...my hair properly should have been oiled and braided neatly, but my father again was saying 'Hurry', so I just looped a buckskin thong about it, and tied it close up against the back of my head, to float loose from there" (Marquis, 1931: 219).

Arrow's clothing is of the everyday variety: a spotted calico shirt, undecorated trade cloth leggings, unbeaded moccasins and the long, Cheyenne style of wool breechcloth, with a simple decoration of ribbon or military braid stitched near the selvedge. Around his waist the Cheyenne has wrapped a trade cloth blanket, a ubiquitous accessory which every man or woman carried when expecting to be away from home.

In his left hand Arrow grasps his bow, and one remaining arrow: there has been a fight, he has expended nearly his full arsenal, and apparently tossed the quiver and bowcase away. The fact that the horses are branded denotes that the fight was with Whitemen. Earlier, when closing with the enemy, Arrow had quickly cut a forked willow, and stripped off the leaves to use it as a coup stick if the opportunity presented. Here, he uses it to lash the stolen horses onward.

It was also a custom when enemy horses were driven off in large numbers, that the men involved would establish ownership of particular animals by being first to touch them, the same as counting coup by striking with some object held in the hand. The man shown in Plate 146 is doing the same thing. Arrow's intent in this drawing may have been to record how he acquired this particular bay mare, which might have become a gift to some relative when the party returned home.

The grey horse wearing a halter is represented in three-quarter profile, its head twisted back, with successful perspective suggested by the curving line of its mane. It is rare to see such an early example of perspective in the ledger-art genre, an indication of Arrow's technical virtuosity as an artist. Other efforts at perspective appear in Plates 32, 67, 68, 94, 120, 144 & 148.