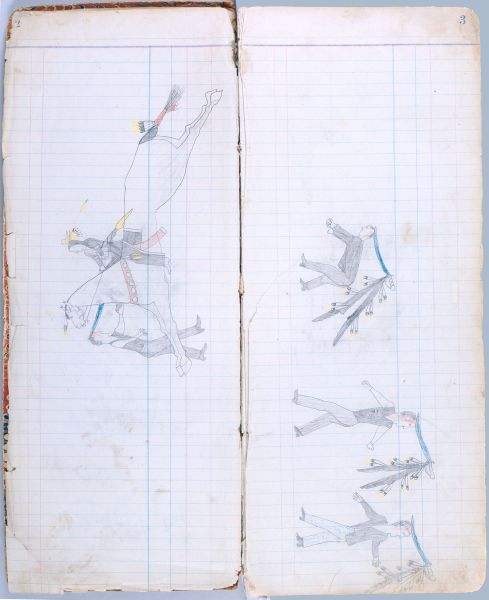

PLATES 2-3

Ethnographic Notes

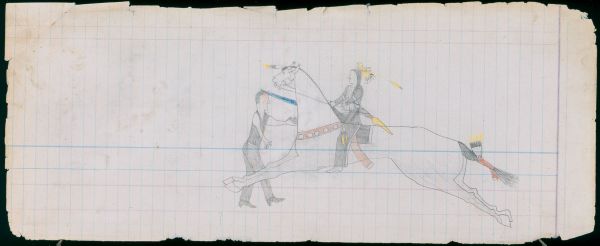

By comparison with Plate 13, which combines the stuffed hawkskin head ornament shown here, with the red and black hair wrappings depicted in Plate 1, it can be judged that all three compositions are self-portraits by Arrow. The stuffed skins of birds of prey, particularly hawks and kingfishers, were favorite war talismans among the Cheyennes. Often associated with visionary experiences, such avian hunters were thought to impart their own, swift-killing attributes. George Bent remembered:

"War paints or war charms were bought from Medicine men by young warriors. Paints and charms went with painted shields. Medicine Spears or Lances had paints to go with them [too].

Medicine men also made charms to wear around the neck, and on scalplocks. Shields, war bonnets and charms were supposed to ward off bullets and arrows in battle. Charms were also made to keep away any kind of sickness" (Bent, 1904-1918: Jan. 24, 1906; May 10, 1906).

More detail in regard to usage of such birdskins is revealed by the Northern Cheyenne historian John Stands in Timber, in describing Cheyenne preparations for the Battle of the Rosebud, June 17, 1876:

"While the scouts were going ahead...the warriors behind them began getting ready for battle. Many had ceremonies to perform and ornaments to put on before they went into war...many...used mounted birds or animals and different kinds of charms...The warriors depended on being protected by the power that came from them...Some were wonderful medicines, like the mounted hawk of Brave Wolf's that he had been given after fasting at Bear Butte. He would tie it onto the back lock of his hair and ride into a fight whistling with a bone whistle. Sometimes on a charge the bird came to life and whistled too..." (Stands in Timber, 1972: 184-85).

Although Arrow's protective hawk is shown rather small, suggesting that it might be a kestrel, called by the Cheyennes aenohes ("little hawk"---Moore, 1986: Fig. 4), the wide-spread, black-tipped tail feathers make it more likely that it is a rough-legged hawk, hoestom (ibid.), perhaps a juvenile. Moore says further: "...there are scores if not hundreds of...hawk names used as personal names, describing hawks which are alleged to be singular and unique" (Moore, 1986: 185).

Flying back from a thin buckskin thong attached to the back of the hawkskin, above its heart, is a yellow-dyed fluff. The dots along this yellow thong indicate that it is wrapped at intervals with porcupine quills. The protective spirit of the hawk, and in fact the soul of the wearer, was supposed to inhere in this fluff, which would be practically impossible for an enemy to strike with any missle. Compare the reasoning given by Grinnell, 1923, II: 120.

Among the earliest descriptions of Cheyennes on the Southern Plains, is this from the Long expedition, in August 1820:

"They...regard long hair as an ornament...depending in many instances, particularly in the young beaux, to their knees, in the form of queues, one on each side of the head, variously decorated with ribbon-like slips of red and blue cloth, or colored skin" (James, 1823: 180).

Precisely these hair wrappings are employed by Arrow: the slips of red and blue cloth (Plates 1, & 13), and in this Plate rich otterskin, with the flesh side of the pelt painted yellow. A wrapping of red cloth secures the bottom of this otterskin.

An interesting detail in regard to the utility of these hair wraps is contributed by Col. Richard I. Dodge, who was an officer of the United States Army serving in the country of the Southern Cheyennes precisely when Arrow was making these drawings:

"The central and northern Plains tribes part their hair in the middle, and confine it in two long tails, one over or just behind each ear. These---are wrapped with a long and narrow piece of cloth, or skin cut in strips, the folds of which furnish receptacles of which the Indian makes great use. I have often been surprised to see an Indian pull out from his hair a letter, or a bundle of matches, or a stick for cleaning his pipe; anything that can be carried in a narrow compass is sure to go in his tails" (Dodge, 1882: 304).

Here, Arrow wears the same breechcloth and undecorated wool leggings as in the previous Plate. Again, his moccasins are undecorated as well. He has a long-sleeved shirt of dark cloth accented with armbands of nickel-silver above each elbow. On his chest is worn a breastplate of conical, tubular beads made of conch shell or bone, called "hairpipes", laced together in four narrow rows, between strips of harness leather. On his belt is a revolver carried in the type of narrow, black-leather holster issued to cavalrymen and officers of the U.S. Army (compare Woodhead, 1991: 201 & 205).

Here, as in the previous drawing, Arrow sits upon a simple pad of folded, dark-blue wool cloth, with the white selvedge indicated. Wooden Leg recalled: "Women used saddles for riding. They sat astride...Old men likewise used saddles. But young men always rode bareback" (Marquis, 1931: 79-80). As we shall see, that was not always the case; but for the rigors of combat, when ease of movement might mean the difference between life and death, a simple riding pad was preferred.

The forked ears of Arrow's horse indicate that it was a fast runner, reserved for war or for the chase. Again, the headstall is covered in costly plaques and conchos of nickel-silver, or perhaps coin silver hammered thin, and fashioned to the purpose. In the 1870's, Col. Dodge observed:

No single article varies so much in make and value as the bridle...[It] may be a mere head-stall of rawhide attached to a bit...the whole not worth a dollar; that of another may be so elaborated with patient labor, and so garnished with silver, as to be worth a hundred dollars" (Dodge, 1882: 251-52).

The horse's tail is wrapped with red trade cloth, and accented with golden eagle tail feathers tipped with spots of white ermine fur, or burnt-gypsum glue, and yellow-dyed horsehair. In combat, as in hunting, when heedless racing through brush or other obstacles might be required, and a horse's long tail hair could become tangled and trip the animal, a standard precaution was to bind the tail.

Arrow's mount is further garnished with a breastband of red wool cloth on which are mounted circular decorations. These might be nickel-silver conchos, like the one visible on the horse's bridle. However, it is more likely that they are intended to represent circular trade mirrors. As will be demonstrated in the commentary for Plate 7, Arrow was a member of the Elk or Crooked Lance warrior society. The Elks "seemed especially to reverence the Thunder" (Grinnell, 1923, II: 59), and their regalia consequently bore multifarious expressions of lightning. As these mirrors on the horse's breastplate reflected sunlight, they gave the impression of lightning flashing from the animal: or conversely, that he was surrounded and protected by a storm of electricity. Such mirrored references to lightning are a constant feature of Elk Society regalia.

In his right hand Arrow wields an 1860 model U.S. light-cavalry sabre (compare Woodhead, 1996: 78-79). This is shown in great detail three times in Plate 3, where the same weapon sequentially strikes three enemies, as Arrow is inferred to be pounding by. As it was swung in combat, the blade and hilt of such a sword might often flash reflected sunlight. As much as the deadly nature of the blade, the fact that it appeared to shoot lightning as well was coveted, and conjured with by the Elks.

Hanging from the sword hilt is a complete otterskin, split down the spine, and each half hung with three pairs of golden eagle tail feathers tipped with yellow-dyed horsehair. There are a total of twelve feathers, or a complete tail---an ostentatious display, since a good horse was valued at from one to three eagle tails (Grinnell, 1923, I: 299, 302 & 306). At the right edge of Ledger Page 3, the artist has shown one of the otter strips flipped over, to display the flesh side of the pelt painted yellow. In endless combinations, Elk Society members expressed their group identity in colors of black and yellow (Marquis, 1931: 154).

Although strangely none of the previous studies of Cheyenne warrior societies mentions the use of sabres, these weapons appear in hundreds of Cheyenne drawings, and are decorated in distinctive and often recognizable ways. As early as 1846, they were reported in use among the Southern Cheyennes:

"The squaws and men were dressed in different and more fantastic styles than ever. Some with the horns and skin of a buffalo attached to their own heads; others, with jackets of red and blue cloth, carried swords and lances" (Garrard, 1955: 90).

Although this passage might well refer to the Bowstring Society, rather than the Elks (the buffalo headdresses identify Red Shield Society members), nonetheless the combination of warrior society swords and lances is instructive.

Shortly, in regard to Plate 5, evidence will be discussed which places the events depicted in this ledger during 1874-75. Although the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867 had reserved all wild game south of the Arkansas River to use of the Indian population, and expressly forbid the presence of non-Indian hunters in their country, during the 1870's an ever-increasing flood of White hide hunters invaded the Southern Plains. Supplied out of the frontier town of Dodge City, Kansas, by 1872 there were hundreds of hide-hunting outfits poaching the Cheyenne buffalo herds, taking only the hides and some of the tongues, and leaving hundreds of thousands of carcasses merely to rot, polluting the countryside. One Dodge City firm alone shipped over 200,000 hides to eastern markets in the spring of 1873 (Hyde, 1968: 756, n. 4).

Well aware that their people must starve if the wanton slaughter continued, a delegation of Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa and Comanche chiefs traveled to Washington, D.C., in the Fall of 1873, to complain of the government's failure to prevent these violations, and to warn that war must inevitably result. President Ulysses S. Grant solemnly promised these chiefs that the invasion would end, but the army did little or nothing to remove the offenders, often instead providing them with protection and assistance.

So many of these hide hunters moved into the Texas panhandle during the winter and spring of 1873-74, that enterprising merchants followed to open a store, saloon and blacksmith shop at the site of an old trading post called Adobe Walls, on the Canadian River. The tribes could brook no more, so a massive war party of Comanches and Cheyennes, with a few Kiowas and Arapahoes, attacked the settlement at Adobe Walls on June 27, 1874.

Most of the hide hunters and merchants retreated within the thick walls of the old adobe post, where the Indians were unable to drive them out. After a battle that lasted about nine hours, from dawn to mid-afternoon, only three of the Whites had been killed, but the Cheyennes had lost five men and the Comanches four, their bodies lying so close to the walls they could not be recovered. Another wounded Cheyenne died later (Hyde, 1968: 353-60; Grinnell, 1915: 321-24). The hide hunters cut off the heads of the dead Indians and left them on poles when they abandoned the site a few days later.

Immediate complaints from the hide hunters, and their merchant backers at Dodge City, and other commercial interests in the East, brought orders for the U.S. Army not to arrest the violators of the treaty, but to attack and subdue the Southern Plains tribes instead. Some of the hide hunters who had caused the entire conflict, such as Billy Dixon, were even retained as scouts by the Army (Hyde, 1968: 359, 361).

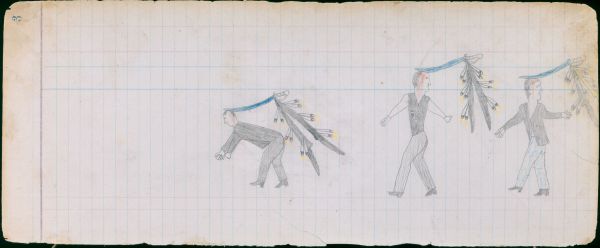

Conflict now erupted all along the Southern frontier, with Cheyenne war parties taking a leading role. The likelihood that the event shown in Plates 2-3 occurred during 1874-75, combined with the fact that four White civilians are shown as victims of a Cheyenne party, suggests a likely identity for these men. George Bent recalled:

"On July 3 a small party of Cheyennes attacked Patrick Hennessey's wagon train near what is now Hennessey, Oklahoma [20 miles south of Enid]. I knew Pat Hennessey very well...He was warned not to make this trip, but being utterly fearless himself, refused to see any danger. Hennessey's train was loaded with goods for Agent James Haworth of the Kiowa and Comanche Agency. Hennessey was killed, also his three teamsters: George Fand, Thomas Calloway and Ed Cook. A large party of Osage buffalo hunters came up just after the fight and threw Hennessey's body in the grain wagon and burned it. They also secured most of the plunder" (Hyde, 11968: 360-61).

Implicit in this account is the fact that the Cheyenne party must have been very small, or they would not have ceded the spoils of this attack to their Osage enemies. The Cheyennes must have been forced to decamp as soon as they saw the Osages approaching. Few numbers lends credence to Arrow's claim that he alone struck all four of the teamsters. The Cheyenne attack certainly took the Whitemen unawares, for as shown by Arrow none has had time to grab any of the weapons that must have been close at hand. The fact they are all afoot indicates the attack was made either early in the morning, or at evening, when the men were encamped. The present town of Hennessey is on Turkey Creek, a locale that also suggests a campsite.

The one teamster with courage enough to face the Cheyenne's charge would be Patrick Hennessey himself. When Arrow's slashing sabre cleft Hennessey's skull, the others panicked and ran, the Cheyenne swooping after: three quick strokes and the tale was told. Yet superficial as Arrow's contact with these men must have been as he dispatched them, they were not generic enemies to him. Ironically, perhaps, the killer of Pat Hennessey, George Fand, Thomas Calloway and Ed Cook has left individual portraits of his victims, each depicted in distinctive dress (again, the texture of corduroy is represented), and even the differences of haircut, or whether a man's hair was straight or curly, has been recorded by the artist's discerning eye.

Interestingly, although George Bent was himself a member of the Elk Society, he failed to recall that the war party which attacked Hennessey's train was comprised of Elks. Perhaps Bent enjoyed a selective memory.

The arrangement of the two pages of this Plate provides a classic example of the way in which Cheyenne artists conceptually modified two-dimensional space, in order to express action in three dimensions. Commonly, Cheyenne drawings flow from right to left, and the composition is arranged with the bottom toward the spine of the book. In working, therefore, the artist turned the volume sideways, and drew on the "top" or far page. Usually, these will be the odd-numbered pages, if printed numbers are present (see the photograph of Wooden Leg at work in Afton, et. al., 1997: xx; or Maurer, 1992: 42).

If the planned composition could be restricted to a single page (as in Plates 5, 7, 9, 13 etc.), then nothing would be drawn on the even-numbered facing page. The completed, odd-numbered page would be turned down toward the artist, and the next drawing made on the following odd-numbered page.

If as we see here, however, the action overlapped, requiring more than a single page, the composition would be completed by revolving the open volume 180 degrees, and continuing on the even-numbered facing page, again with the bottom of the drawing oriented toward the spine. The consequence is that action on right-hand pages of the ledger flows toward the top of the volume, while action on left-hand pages flows toward the bottom of the volume.

From a European, compositional standpoint this would seem to be antithetical. In the Cheyenne perspective, however, where circularity always triumphs over the limitations of a flat page, it makes brilliant sense. The viewer assembles the halves of the drawing in his mind, as if he were INSIDE the closed book. This is the same as if he were standing inside a conical tipi, and the composition were painted around him, on the inner surface, or as commonly happened, painted on the draft-screens tied around the tipi circumference (for examples of these see Laubin, 1957: 46 & 94; and Maurer, 1992: Figs. 152 & 153).

When one is standing INSIDE the composition, it is only possible to see part of it at one time. As one views half the lodge (or half of the two-page composition), the other half (the opposite page) is BEHIND him. To view the second half one must turn around inside the tipi; and this is conceptually the same as revolving the ledgerbook 180 degrees. Thus did Cheyenne artists adapt the limitations of a flat format, to suit their circular concept of the world. See further on this point the discussion in Afton, et. al., 1997: 332; and for metaphysical explorations of the same concept applied in other Cheyenne artistic media, see Nagy, 1994b; and Coleman, 1998b.