PLATE 88

Ethnographic Notes

This is a scene of masculine leisure, and as it follows directly after Plate 86, it must also be related to the buffalo hunt sequence. It will be helpful, therefore, to understand what was occurring in a Cheyenne camp immediately after such a hunt; and for that we return to Grinnell's peerless description:

"Meantime the women and children left in the camp have not been idle. As soon as all had eaten, and even while the men were starting out, the women began to catch and saddle the pack horses, and to fix the travois to them. Some of the larger dogs, too, were pressed into service and harnessed to small travois. Each woman set out as soon as she was ready, following the trail made by the hunters. Most of the children accompanied their mothers, the younger ones carried along because there was no one to leave them with, the older boys and girls taken to help in the work, or going for the excitement, or because there would be many good things to eat when the buffalo were being cut up.

"In this throng, which marches steadily along over the prairie, there is no pretense at discipline or order, such as prevailed among the men. It is a loose mob, strung out over a mile of prairie, careless, noisy, unprotected...The women chatter and laugh with one another in shrill tones, or scold at the children or at the horses; the shouts and yells of the little boys, who dart here and there in their play, are continuous...

"When the head of the disorderly procession reaches the crest of the hill above the killing ground a change is seen in the actions of the women and children. They call out joyfully at the sight of the carcasses, and hurry down to the flat. As the women recognise the men, scattered about skinning and cutting up the buffalo, each one hurries toward her husband or near relation to help him. The boys, excited by their surroundings, catch the spirit of their elders, and shoot their blunt arrows against the carcasses.

"Indians are expert butchers, and it does not take long for them to skin the buffalo. The hide is drawn to one side, and the meat rapidly cut from the bones; then the visceral cavity is opened, the long intestine is taken out, emptied of its contents, and rolled up; the paunch is opened, emptied, and put aside with the liver and heart; the skull is smashed in and the brains removed, and of course the tongue is saved. Very likely the liver is cut up on the spot and, after being sprinkled with the gall, is eaten raw; women and children tear off and eagerly devour lumps of the sweet white fat which clings to the outside of the intestine.

"All are jolly and good natured, though hard at work, and the children play merrily about. The old and steady pack horses graze near at hand, while the younger and wild ones are made fast to the horns of the dead buffalo. The camp dogs gorge themselves on the rejected portions, and gnaw at the stripped skeletons. When work on the buffalo is finished, the hide, hair side down, is thrown on a horse, on this the meat is packed; the ends of the hide are then turned up, and the whole is lashed in place by lariats. Then the party moves on to look for another buffalo killed by an arrow belonging to their lodge.

"Before long...young and old are climbing the bluffs toward the camp, leading the laden pack horses, which not only carry heavy loads on their backs, but also drag as much more meat on the travois behind them. On reaching camp the loads are taken off, the hides are folded up, and some of the meat is cut into thin sheets and hung on the drying scaffolds, while the choicer parts are placed in the lodge. When this has been done the hides are spread out on the ground, and the women armed with fleshers of stone or bone, begin to cleanse them of all flesh, fat and blood that clings to them.

"All through the day the loads come into camp, and the scene is one of bustle and hard work. The men who have returned sit in the shade and talk over the incidents of the hunt; admiration is expressed for the skill and bravery of one man, while another, to whom some absurd accident has happened, is unmercifully laughed at by his fellows...

"As evening draws on the feast shout begins to be heard from all sides, the women lay aside their tasks and prepare the evening meal. The feasters gather in various lodges, and people are constantly passing to and fro. At one or two points within the circle of the lodges, some young men and boys have built fires in the open air, and before each of these a great side of fat buffalo ribs is roasting, propped up on two green cottonwood sticks, while the lads lounge about the fire waiting for the meat to cook. When at last it is done, they shear off the long ribs one after another, and with knives and strong white teeth strip from the bones the juicy flesh.

"Everyone rejoices in the abundance of food. Song and dance and light-hearted talk are heard on every side, and so the night wears on. Such was a day's hunting when were killed the buffalo, the main support of the people" (Grinnell, 1908b: 78-81).

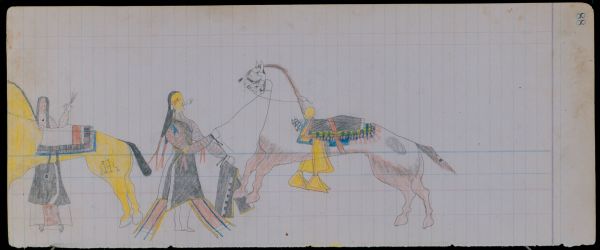

Although essentially a static composition, a "snapshot" as it were of relaxation following the rigors of the chase, this drawing includes a remarkable number of unique depictions of 19th-century Cheyenne culture. Arrow may be recognized from the pair of leggings held in his left hand---previously seen in Plates 34 & 66; and from the small feather tied into his horse's tail; as well as from the horse itself, the white stallion with iron-grey legs and a distinctive spot on his left hip, shown earlier in Plates 32 & 34.

Arrow and his friend, together with the other men of the camp, have been to the nearby stream to wash off the blood and grime of the hunt. Many may have shared a sweatlodge also, a ceremony of prayerful thanksgiving, and internal cleansing, before diving into the tepid, midday waters of the stream; there to linger on the heated sand, allowing the sun to ease some of the bruises and strained muscles occasioned by the hunt. They may have napped awhile, as wives, mothers and sisters worked at their part of the task of livelihood. Somewhat refreshed, wrapped in blankets or buffalo robes, the men straggled back to their own tipis, there to comb and oil their hair, and dress for the evening's festivities. That is what Arrow shows himself doing here.

Significantly, he has dressed his favorite parade horse before himself. The spirited animal, with its distinctive markings, will provide cachet as well as transportation, while he circuits the village during the evening. There is a certain young lady, already introduced in Plate 34, whom Arrow is hoping will notice his stylish figure. To that purpose he has chosen the commercial halter, and over it his flashy, silver-mounted headstall. The horse is girthed with Arrow's colorful Mexican vaquero saddle, its yellow stirrup leathers and tapaderas accented with an outline of red paint. The saddle rests on a folded blue wool blanket seen often before. Over the sharp ridge of the cantle, Arrow has laid a folded Chimayo weaving, fringed and checkered; atop this is a folded wool trade cloth blanket of dark blue (shown as black), with a white selvedge; and both of these pads are secured with an over-cinch of red wool, or possibly red-painted leather.

The red color which overlies the grey of the horse's legs and belly may be paint that Arrow has applied to the horse, just as to the saddle. Note that the black spot on the hip has none of this red; nor did the horse's legs when we first saw him in Plate 32. When Arrow dressed to spy on his sweetheart in Plate 34, however, the red color was also added to the horse.

Hanging from the large saddle horn is a pair of fully-beaded moccasins, the same ones Arrow wore when he killed the Pawnee in Plate 27. Here, they are shown in complete detail, including the undecorated, forked tongues. This is the ONLY such discrete representation of the tribal style of moccasins, done by a Cheyenne artist in the ledger-art genre, known to this author. Compare them with a very similar pair of contemporary Cheyenne moccasins, shown in Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 36.

Wrapped around his waist Arrow has the same dark blue trade cloth blanket, with its edges bound in yellow silk ribbon, first seen in Plate 34. The same yellow binding has been added to his leggings, since we saw them last in Plate 66. This wonderful genre scene is also unique for showing a Cheyenne man putting on his pants. As soon as he has donned the leggings, Arrow will put on his moccasins. His red wool breechcloth is rather extravagantly decorated with blue and yellow silk ribbons, another bit of his courting arsenal---compare Plates 102 & 130. For this occasion Arrow has chosen a shirt of red silk, with an overall pattern of black dots, and wavy, blue pinstripes. Over this he wears a black wool vest, the bottom edge bound in yellow silk ribbon; and brass armbands accented with red silk ribbons at the elbows.

Arrow has washed and repainted his face with the same design worn earlier---a yellow ground, with a short, vertical black line on either temple. Over this is added a narrow triangle of red, diverging from the outer corner of each eye. His dentalium shell choker with yellow-leather spacers was seen earlier in Plate 32.

Arrow's hair, parted down the center of his head, is gathered into a bundle on either side, and several inches at the bottom ends are wrapped with red cloth. This is a preliminary step. Once he is completely dressed, he will add elaborate hair wraps, either of otterskin or plaited cloth, such as those seen in many of his other self-portraits. An important detail not represented in this profile is his scalplock, a small circular area of hair on the crown of the head, plaited or separately wrapped, and never omitted by any self-respecting Cheyenne man of the 19th century. Compare the unusual rear view which Arrow gives of hinself in Plate 144, where the complete hair arrangement is carefully shown.

Two interesting details complete Arrow's ensemble. Narrow strips of zigzag, twisted otter fur are tied around each wrist. These undoubtedly are related to his membership in the Elk Society, and may denote his status as a Lance Owner of that organization---compare his otter-wrapped straight lance in Plates 7, 27 & 163, where similat twisted strips of otter fur hang along the shaft. On the lance, each of these strips is terminated with a dewclaw; Arrow's "bracelets" here may also have dewclaws at the tips, although these terminal triangles are shown somewhat smaller than on the lance.

The final detail of interest in Arrow's preparation for a "night on the village", is the broken yellow line which runs from his right shoulder, diagonally down across his vest. This represents a bandolier of brass beads, which encircles his torso. The blue bundle of gathered cloth at the right shoulder is attached to this bandolier, and contains important ingredients in Arrow's campaign for the evening:

"Tied to the necklet or to the shoulder girdle, or perhaps to the hair, most men carried about with them one or more little bundles of medicines, some spiritual---i.e., effective by their mysterious power---others with curative properties...The old stories tell us that people learned of the various medicinal plants, and of the uses to which they were to be put, by means of dreams..." (Grinnell, 1923, II: 134).

Elsewhere (1923, II: 170, 186-189-90) Grinnell lists favorite ingredients used by the Cheyennes for purposes of courting: Vih'o ots (sweetgrass); Me e mi a tun (sweet pine); Moin a mohk shin (horse mint); and Ononi wonski a mohk shin (prairie dog perfume). Some personal combination of these is likely what Arrow carries on his bandolier.

The people in Cheyenne society who were considered special recipients of such dreams about "romantic" plants, and knowledge about the intricate details of courting, and how to win the affection of another, were the He'emaneo, or "halfmen-halfwomen". These individuals were very highly regarded, and sought out by young people of both sexes for advice on matters of the heart, and the preparation of effective perfumes and love charms (Grinnell, 1923, II: 39-44). Arrow shows himself consulting a famous He'eman in Plate 148. Very likely the powerful perfume with which he has clothed himself here was obtained from the same source.

In the portrait of his friend at the left---possibly Young Bull Bear, his Nisson relative and Elk Society brother, who appears in Plates 90, 100, 112, 134, 136 & 163---Arrow has advanced light-years from the tentative attempts at full-frontal perspective in Plate 68. This is a very mature and convincing figure. In Plate 148, Arrow will do even better. Both of these frontal depictions incorporate shifts in perspective: although the entire figure above the ankles is shown in lateral view, the moccasined feet are represented as if the artist were looking directly down on them.

The smiling visage of this man is seen over the back of his buckskin mare. Unlike many of the profile portraits created by Cheyenne ledger artists, including Arrow himself, personality, emotion and intent are conveyed by the facial features represented here. The man is smiling because he has been joking with his friend, and they both have plans for the evening.

The buckskin carries an Indian-made saddle with low pommel and cantle bows. It is identical in type to the saddle used by Arrow in Plate 80. One rawhide-covered stirrup is shown in negative-image profile against the dark blue trade cloth blanket wrapped around the man's waist. Under the saddle is a folded, blue blanket. On top of the saddle the Cheyenne has laid a fringed and folded Chimayo weaving, then a folded, red wool trade cloth blanket, and over these a folded piece of white canvas. If he succeeds in finding a female companion for the evening, they will have a soft seat; and many blankets to spread upon the ground. Arrow, we see, has given serious thought to similar preparations.

While Cheyenne women were held to a strict code of chastity, Cheyenne males generally were not. There were often captive women living in Cheyenne communities; while adopted into the tribe, still they were not considered "real" Cheyennes, and if they chose to transgress the sexual code, not much was thought of it. Also, women of allied tribes were often available, and the focus of sexual attention from ardent young Cheyenne men. In the summer of 1865, for example, during the Powder River War, most of the Southern Cheyennes moved up into Wyoming to join the Northern Cheyennes, the Lakota Sioux, and the Arapahoes in attacking Whites, Crows and Shoshones along the Platte valley and elsewhere. In an important passage that was omitted from George Hyde's LIFE OF GEORGE BENT, the subject of that biography, then a lusty young Cheyenne of twenty-two, recalled:

"[August 1865] The Indians after the Platte Bridge fight moved about in search of buffalo, and to get meat...There were so many Indians, they had to scatter to find buffalo. All the young men ran around a good deal to different camps to court young women, both Sioux and Cheyennes. We were also having Scalp Dances---had just killed [some] Shoshones" (Bent, 1904-1918: 17 Nov 1915).

A brief review of the social purposes behind a Scalp Dance (Grinnell, 1923, II: 39-44) will confirm that the intent was to allow crowds of young men and women to mix socially in a semi-anonymous night setting lit only by bonfires, and where couples might discreetly vanish into the darkness if they chose. The piles of bedding which Arrow and his comrade have loaded on their horses indicate that "vanishing" is what they hope to accomplish for the evening. Large villages of Southern Cheyennes, Kiowas, Comanches and some Arapahoes were closely associated all through 1874-75. The opportunities for inter-tribal courting must have been inspiring.

An elaborate brand on the buckskin's left hip is rather eloquent evidence for the process whereby Cheyennes acquired many of their horses during the 19th century. In discussing the trade conducted at Bent's Fort, George Bird Grinnell observed:

"It must be remembered that a large proportion of these horses purchased from the Indians, especially from the Comanches, were wild horses taken by the Comanches from the great herds which ran loose on the ranches of Mexico. Practically all these horses bore Mexican brands" (1913b: 183).

It was Comanche horses, originally stolen from Mexican herds, which first lured Cheyennes down to the Southern Plains in the second decade of the 19th century (Hyde, 1968: 31-40. George Bent thought the first band of Cheyennes traveled south in 1826; but the Stephen Long expedition found them already on the Arkansas River in 1820, and they had been there for three years---James, 1823, II: 186-87). In those early years in the South, Cheyenne parties often traveled into the northern provinces of Nueva Espana---present Texas and New Mexico, as well as Chihuahua and Coahuila---after Spanish horses.

By the 1870's, it was rare for Cheyennes to raid into Mexico, but the Comanches and Kiowas regularly did; and then traded some of the horses obtained on their raids to the Cheyennes and the Utes, who in turn traded them to tribes further north. The Bent brothers, their partners, and other early White traders on the Southern Plains had been enthusiastic dealers in purloined Spanish horseflesh, trading them from the Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes and Arapahoes, then driving huge herds east to Missouri, to sell in the American settlements. This international brigandage was condoned and abetted by the American government, always happy to injure Spanish interests in the long-term plan to acquire the Southwest for the United States. The Cheyennes were only one of many, willing links in this chain of Manifest Destiny.

The author has been unable to identify the rancho where this brand documented by Arrow originated. However, it is stylistically similar to several brands in use in Northern Mexico (present Texas), 1771-1810. Compare Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 37, which is based on Jackson, 1986: 646, 648 & 653.

Perhaps the most interesting detail of this drawing is the fact that both men are shown smoking cigarettes. One could search long through the ethnographic literature without any suspicion that Cheyennes---and other Southern Plains tribes---were confirmed users of cigarettes, and at surprisingly early dates. The first group of Cheyennes to travel south, the Hevataneo, or Hair Rope band, met the Stephen Long expedition near the Big Timbers on the Arkansas River in July 1820:

"The Shienne chief...had the good fortune to find a small piece of paper which someone of our party had rejected; with this he rolled up a small quantity of tobacco fragments into the form of a segar, after the manner of the Spaniards, and thus contented himself..."

A few days later, further downriver, the expedition encountered a Bowstring Society war party returning from an attack upon the Pawnees, described earlier with Plates 7 & 17. After a brief parlay, these Cheyennes:

"...now began to ask for tobacco, and for paper to include fragments of it, in the form of segars for smoking..." (James, 1823, II: 188 & 198).

These Hevataneo were then associated with Kiowas, and Kiowa-Apaches ("Kaskaias"). Many Mexican captives had been adopted into both tribes, bringing with them partial knowledge of Spanish riding equipments, metallurgy, glass smelting, and the decadent pleasure of shuck cigarillos. Undoubtedly it had been from such captives, or from Kiowas and Kiowa-Apaches taught by them, that the Cheyennes had learned to roll tobacco in paper or cornhusk.

Arrow's drawing was made about 55 years later, so the Cheyennes had then been enjoying this form of smoking for over half a century. Note the broad smile on the face of Arrow's comrade; and his familiar grip on the cigarette, between thumb and forefinger.

The surviving pages of this ledger document one use---an artistic impulse---that Cheyennes made of paper during the 1870's. Many pages have been torn out of this ledger---48 pages (24 sheets) are missing. In this drawing we may be seeing exactly what the artist, and his friends, did with the rest of the paper. That is, the missing pages may not indicate any missing drawings. The fugitive papers may simply have gone up in smoke.

In this connestion, it is interesting to note which pages are missing in this particular series. The two buffalo hunt drawings (Plates 80 & 86) may have been done on the very afternoon of the chase, while Arrow and his friends were relaxing in camp. While Arrow worked on Plate 80, interested comrades may have sat around to kibitz and joke about events. A good host, Arrow tore two sheets (pages 81-84) out of the ledger, and handed them around for his friends to tear up as smoking papers. These were consumed while he completed Plate 86; and then Arrow documented the progress of the afternoon by showing these sociable cigarettes in Plate 88.

At a time in the social history of the United States when there is great public debate about the morality of cigarette advertising, it is interesting to realize that a young Cheyenne named Arrow had invented the "Marlboro man" a hundred years before the idea occurred to executives of the Philip Morris Tobacco Company.