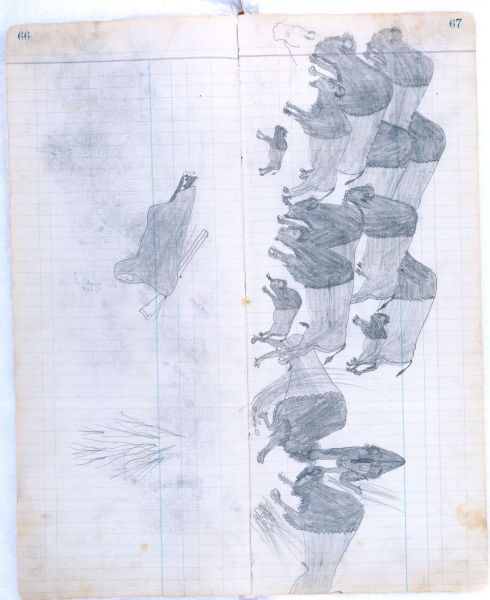

PLATE 66-67

Ethnographic Notes

In one of his most lyrical images, Arrow (whom we recognize from the leggings first depicted in Plate 34) represents himself performing the honorable duty of a special, tribal scout sent to locate buffalo. In notable contrast to every other drawing in the ledger, the artist limited himself to graphite pencil alone, the impact of the composition being even stronger in black and white. Technically, in the figure of one buffalo bull, second from the right, this drawing is significant for its attempt at full-frontal perspective, a very early example in the ledger-art genre. It is also interesting to see the preliminary outline at far left, which the artist apparently disliked, and abandoned.

For all Algonkian-speaking peoples, including the Cheyennes, buffalo are believed to be owned by subterranean Powers. They are engendered deep in the earth, and herded in sacred caves called Heszevoxsz (Schlesier, 1987: 4-6; Petter, 1915: 194, 209, 218; Moore, 1974: 163). In annual cycles of benevolence, and also in special response to the great ceremonies of the Sacred Arrows, the Medicine Lodge and the Massaum, Maheo the Creator sends buffalo out onto the surface of the earth for the livelihood of the Cheyenne People.

Col. Richard Dodge, military warden of the Southern Cheyennes in the late-1870's, learned something of this belief:

"The Cheyennes and Arrapahoes have a curious tradition...regarding the buffalo. They believe that these animals are created within the bowels of the earth; that every year when the young grass appears herds of thousands pour out of two holes in the ground and, under the direction of the Good God, depart on their long journeys to the countries of those tribes whom he desires especially to favor, or who have the most potent medicine men. They believe that these holes are on the "Staked Plains", south of the Canadian, and east of the Pecos; and there are now living men of both these tribes who will take oath after their most solemn forms, that they have been to the spot, and seen the buffalo coming out in countless throngs... Stone Calf, a chief of the Southern Cheyennes, intelligent and influential...last spring [1880] when begging for food, and urging me to permit him to go to the "Staked Plains" for buffalo...assured me most solemnly that he knew where these holes are, and would be able to get all the buffalo he wanted. I attempted to rally him on the absurdity of his belief, but found myself in a very few moments in such position as if I had attempted to banter a High Churchman on his belief in the Trinity, or a Roman Catholic on the authenticity of a miracle.

"He was in real, solid earnest, and as I never interfere in the religious beliefs of people, I backed down as gracefully as possible" (Dodge, 1882: 580-81).

The 19th century migratory patterns of the buffalo made this theory seem entirely logical. In winter, the animals were scarce; but early in the spring they began a northward movement, first a few animals, then more, then seemingly overnight millions of them, in columns fifty miles wide. The great herds passed to the north, then dispersed, where they spent the summer. In autumn and early winter the herds migrated south again; but in small, discrete groups driven ahead of snowstorms, so that they often passed unnoticed; and never appeared to approach the stunning volume of the spring. So each year it seemed that a new flood came from the south.

There are places on the Plains---deep canyons, like Palo Duro in the Texas panhandle---which cannot be seen until one stands nearly at the edge of their escarpment. Climbing up side ravines from such sunken terrain, streams of buffalo could seem to leap literally out of the ground; and there is no doubt that individuals of many tribes witnessed such miraculous appearances, again and again.

Nor should we discount the stories of appearances from actual caves, for buffalo are curious, and wont to explore. It is likely that some animals really entered cave mouths, sheltered a while and left their droppings. If Indian witnesses then saw these buffalo actually emerging from a cave, even once, the theory would seem above any human question or reproach.

One place where Cheyenne people, in the latter-18th century, almost certainly did see buffalo coming out of the earth is Ludlow Cave, in the North Cave Hills of South Dakota. On a nearby cliff face they carved perhaps the greatest surviving petroglyph in North America---seven feet high, and fifteen feet long, the figure of Esevon, Mother of All the Buffalo. A newborn calf is protected between her legs, and the afterbirth is streaming down (see Cowdrey, 1999: Fig. 31; or Keyser, 1984: Fig. 14; and Keyser 1987b: Fig. 1). A pattern of buffalo hoofprints is incised within the figure: other animals ready to emerge, and sustain the Cheyenne People. These hoofprints are very similar to those shown by Arrow on the war shields in Plates 27 & 165.

Some scholars have attributed this petroglyph masterpiece to the Mandans; but Ludlow Cave is north of the Black Hills, on the headwaters of the Little Missouri River, precisely where the Cheyennes were trapping antelope and eagles in the late-1700's (Bowers, 1950: 210; Grinnell, 1923, I: 252, 278-83). Southern Cheyennes were still returning there to pray and to hunt as late as 1864-65 (Grinnell, 1923, I: 289; Hyde, 1968: 196, 243). Northern Cheyennes doubtless traveled there later, and more often (Marquis, 1931: 58, 88).

In Arrow's drawing of the herd, the fact that three bulls are fighting---pawing clouds of dust into the air, and butting heads---denotes that the season is August, or early September, during the rut, for the cows and calves travel separately at other times.

Wooden Leg, an Elk Soldier like Arrow, recalled:

"To organize for the tribal buffalo hunt [a] council was called...usually...at and after darkness, by the light of a great bonfire. The big chiefs regularly would tell the leading warrior chiefs, 'We want four good and reliable warriors to scout and discover the location of a buffalo herd'. When the warrior leaders had nominated these four, the old man herald moved on horseback through the camp calling out their names and the duty put upon them. They went to the council and there received their instructions through their warrior chiefs. They performed the scout duty according to their orders---nobody ever dared refuse to go---and upon their return a report was made to the old man herald" (Marquis, 1931: 62-63).

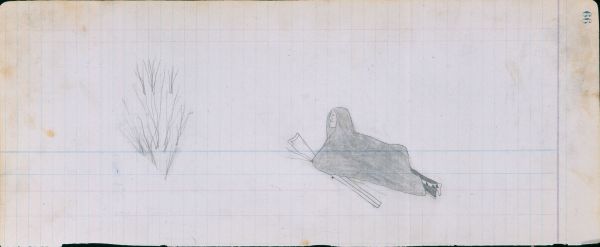

Arrow shows himself secreted, just at the crest of a hill. His head and shoulders are covered by a blanket to obscure any outline, and he is peering through some bushes at the herd below. On his face is a satisfied smile: he has succeeded in his commission; his people will have plenty of food; and they will mention his name for this good work. Quietly he slides back down the hill to his waiting horse, and then returns to make his report to the village herald.

The receiver below his rifle barrel identifies it as a Winchester carbine, a significant improvement over the Ballard of earlier drawings. In subsequent drawings, Arrow shows himself using both 1866 and 1873-model Winchesters; this weapon might be either of those.